Dominicans have a reputation for being among the friendliest people you’ll meet. They exude passion–in the way they speak a mile a minute, the way they dress, and dance, and in their embrace of their fellow human being, be it neighbor or visitor. Their explosive energy could be explained in their mélange of Taino, African, and European roots. But to boot, European, Asian, and Middle Eastern communities have influenced and enriched the DR’ culture-scape since the 19th century, turning the population and culture into a fascinating melting pot. You’ll see our numerous influences showing up across regions in food, music, celebrations, and customs.

TAINO ORIGINS

The DR’s first inhabitants were the valiant, skilled indigenous Taino–Arawak Indians who first settled on this side of the island before Christopher Columbus and the Spaniards arrived. They ran multiple kingdoms–each ruled by a chieftain or cacique–observed class distinctions, and coexisted peacefully. There were several valiant Taino leaders who stood up against Spanish colonization and slavery. Cacique Caonabo, from the Samaná region, was first to lead a revolt.

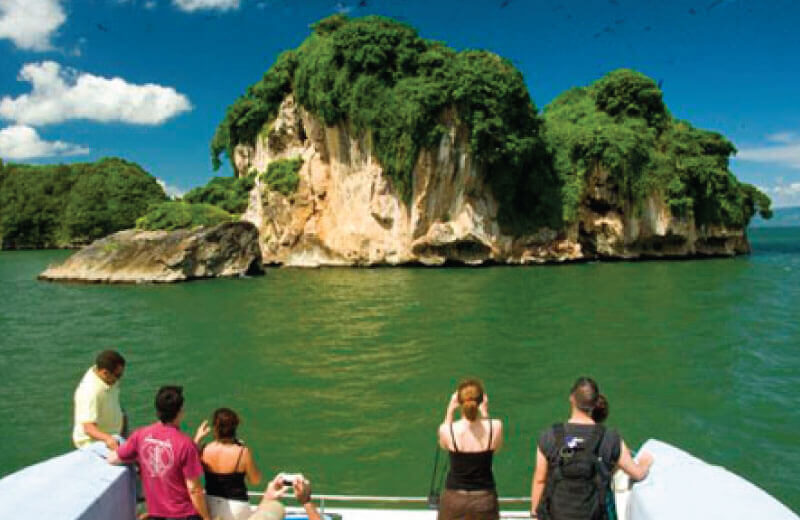

The Taino practiced complex agriculture, but were also talented artisans, and believed in medicinal plants and natural remedies. Today, their only remaining signs are in the caverns where they left pictographs and petroglyphs–mainly in Samaná, Bayahibe, San Cristóbal, and Enriquillo–and in the various museums around the country, particularly the Museo del Hombre Dominicano in Santo Domingo, and the Museo Arqueológico Regional Altos de Chavón in La Romana.

IMMIGRANTS

The Dominican Republic’s welcoming nature, coupled with historical events, has resulted in several key migrant communities settling and blending into the DR’s cultural makeup. Some are more recent transplants, whereas other settled here in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Sosúa counts with a Jewish community–about 600 Jews arrived between 1940-1945, escaping the Nazi persecution during World War II, thanks to visas offered by the Dominican government. The Jewish Museum in Sosúa commemorates their journey and their contributions to the north coast’s meat and dairy industries.

Southeast of the DR, in San Pedro de Macorís, are the Cocolos–Afro-descendants from neighboring Caribbean English-speaking islands, such as Tortola, Antigua, and St. Vincent, among others, who migrated to the DR in the late 19th century. They worked as laborers and technicians in the DR sugar production industry. In Samaná, descendants of freed African-Americans moved to the DR in the 19th century, and continue to practice their religion and rituals.

In the central mountains, you’ll find the Japanese community in Constanza, and a French and Italian community on the northern Samaná Peninsula.

The DR is also inclusive of a small but solid Lebanese, Syrian, and Palestinian communities who migrated from the Ottoman Empire in the early 20th century. They slowly integrated into Dominican culture, rising into high political ranks.

All of these groups have contributed a great deal to the growth and cultural makeup of the DR, reflected in the food, culture, and events around the country.

DOMINICANS TODAY

It won’t take you long to meet locals, or notice the Dominican way of living. While modernism and globalization have modified the way of life in the big and small cities, Dominicans remain the same in their people-to-people interactions. Courtesy and hospitality are core values, particularly in the countryside. Coming to the aid of visitors or a neighbor, and sharing a plate of food are considered normal. Family is of the utmost importance, to be cared for and cherished. Head to the beach or to the river on the weekends, and you will see how Dominicans love to spend their free time with their loved ones, cooking outdoors and sharing jokes. Affectionate in words and action, romance runs in the Dominican’s blood. Life is to be shared, and lived fully.

TRADITIONS

While certain traditions are less practiced in the cities than in the past, the importance of two major seasons remain–particularly in the countryside–and are celebrated in family: Christmas and Easter.

Each of these holidays represents a symbolic time for Dominicans to head to their respective hometowns and families, and spend it around their loved ones, cooking and enjoying traditional dishes, dancing, and relaxing.

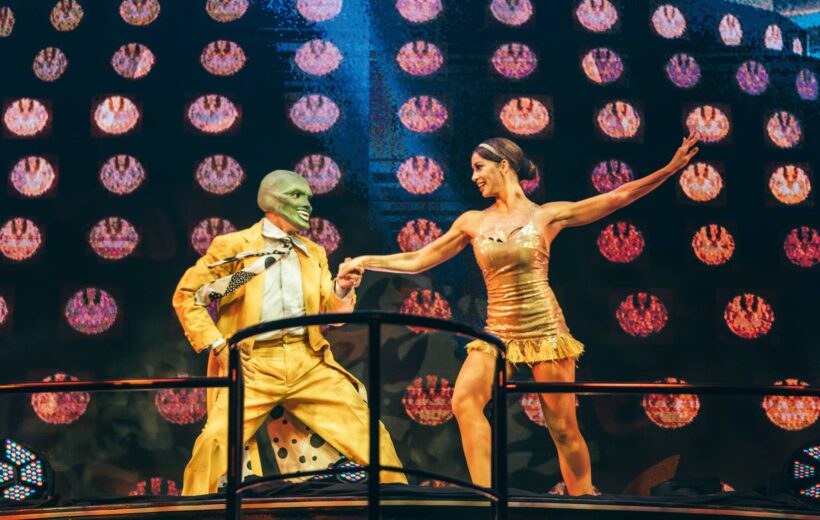

Christmastime is one of the most festive times of the year, aside from Carnival in February. This is particularly visible in the countryside, when families gather and visit from house to house to eat, drink, and dance. On Christmas Eve, entire pigs on a pit are slowly roasted out in the backyard all night long, while families listen to music and share drinks, with everyone keeping an eye on the meat. The tradition is to stay up and celebrate until dawn, when the meat is finally cooked.

Eastertime, the other longest holiday weekend, is when Dominicans escape their daily routine, much as they do for Christmas. While some head to the beach rather than practice religion, traditions remain: celebrating Semana Santa by going to church on Good Friday, and Holy Saturday, but also enjoying copious bowls of habichuela con dulce, a Dominican sweet beans dessert typical at this time of year.

RELIGION

A majority of Dominicans are Roman Catholic, but there are also other Christian denominations, including Jehovah’s Witnesses and Evangelists. Various forms of syncretic religion, an African influence, are still practiced in the countryside. No matter what religion it is, Dominicans are a people of faith with a strong belief in God. You will hear references to that effect in their every day language.